Cardiovascular Disease

As a whole, cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the leading cause of death globally, representing 32% of all deaths.1,2 CVD can be caused by a variety of lifestyle, environmental, and medical factors.

Despite lipid-lowering therapies (LLTs), death rates due to cardiovascular events continue to rise. Heart attack and stroke claim more lives each year than cancer and chronic lower respiratory disease combined.6

By the Numbers

20 million

CVD deaths globally each year2-4

1.58 seconds

someone dies from CVD, up 22%

from 2010.1-4

85%

Approximate percent of global

CVD deaths due to heart attack

or stroke. One-third of these

deaths occur in people under 70

years of age.1,5

Risk Factors of Cardiovascular Disease

Low-density Lipoprotein Cholesterol (LDL-C)

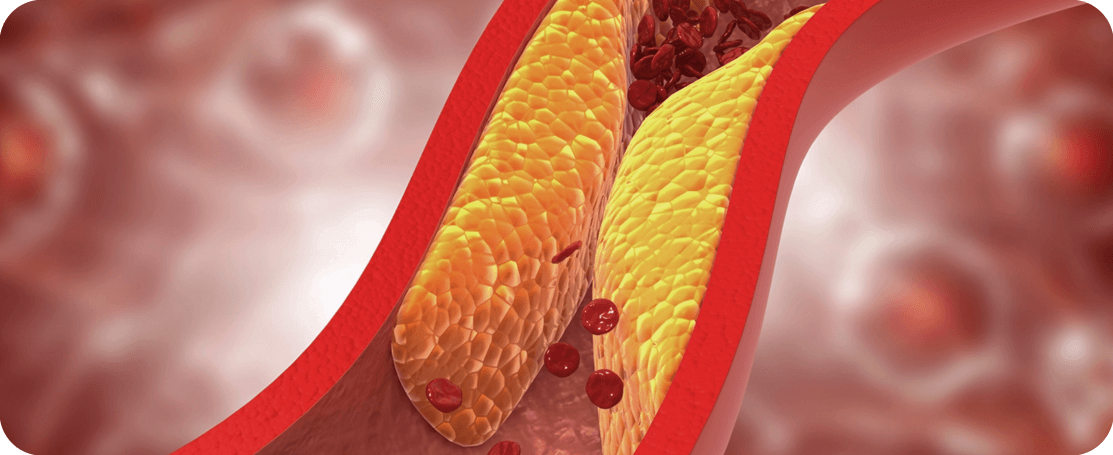

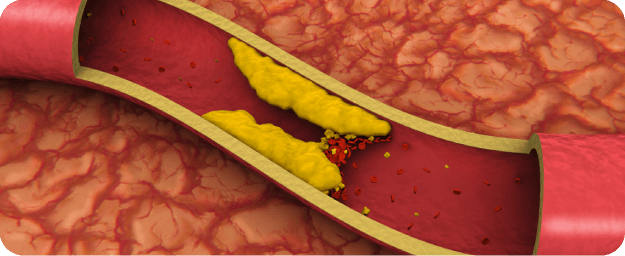

Atherosclerosis—which can lead to blood clots and subsequent cardiovascular death, heart attacks,

or strokes—is predominantly caused by elevated LDL-C levels.7-10 If elevated, these particles can

become trapped in the arteries, forming atherosclerotic plaque.7,9 Over time, this plaque can build,

increasing the risk of cardiovascular events like heart attacks and strokes.9

LDL-C builds up in artery walls.

Deposits can cause vessels to suddenly become blocked—or blood

clots to form—causing a heart attack or stroke.

Lower is Better

Intensive reduction of LDL-C is crucial to halting

atherosclerotic plaque buildup and lowering the

risk of CVD.10 Reducing and maintaining the

reduction of LDL-C over time is associated with

fewer major cardiovascular events, including heart

attack or stroke.11-15

However, despite the availability of LLTs, many

patients are still at risk for cardiovascular events.

More than 75% of patients with atherosclerotic

cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) do not achieve

their risk-based LDL-C goals and remain at risk for

cardiovascular events.16,17

Additional Risk Factors

Associated with CVD

Even patients who have met their LDL-C goals are

at risk for cardiovascular events.18-21 This suggests

additional factors are at play, such as lifestyle

choices, tobacco use, and obesity, as well as:

- Inflammation

- Thrombosis

- Triglyceride levels

- Elevated Lp(a) levels

- Type 2 diabetes18-21

1. Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs). World Health Organization. June 11, 2021. Accessed March 5, 2024. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cardiovascular-diseases-(cvds) 2. The top 10 causes of death. World Health Organization. December 9, 2020. Accessed March 5, 2024. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/the-top-10-causes-of-death 3. Woodruff RC, Tong X, Khan SS, et al. Trends in cardiovascular disease mortality rates and excess deaths, 2010-2022. Am J Prev Med. Published online November 14, 2023. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2023.11.009 4. Martin SS, Aday AW, Almarzooq ZI, et al. 2024 heart disease and stroke statistics: a report of US and global data from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2024;149(8):e347-e913. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000001209 5. Cardiovascular diseases. World Health Organization. Accessed January 22, 2024. https://www.who.int/health-topics/cardiovascular-diseases#tab=tab_1 6. Tsao CW, Aday AW, Almarzooq ZI, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2023 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2023;147(8):e93-e621. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000001123 7. Feingold KR. Introduction to lipids and lipoproteins. In: Feingold KR, Anawalt B, Boyce A, et al, eds. Endotext [Internet]. MDText.com, Inc; 2000–. Accessed March 5, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK305896/ 8. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Blood cholesterol: causes and risk factors. Updated March 24, 2022. Accessed February 12, 2024. https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/blood-cholesterol/causes 9. Goldstein JL, Brown MS. A century of cholesterol and coronaries: from plaques to genes to statins. Cell. 2015;161(1):161-172. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2015.01.036 10. Nurmohamed NS, Ditmarsch M, Kastelein JJP. Cholesteryl ester transfer protein inhibitors: from high-density lipoprotein cholesterol to low-density lipoprotein cholesterol lowering agents? Cardiovasc Res. 2022;118(14):2919-2931. doi:10.1093/cvr/cvab350 11. Ference BA, Ginsberg HN, Graham I, et al. Low-density lipoproteins cause atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. 11. Evidence from genetic, epidemiologic, and clinical studies. A consensus statement from the European Atherosclerosis Society Consensus Panel. Eur Heart J. 2017;38(32):2459-2472. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehx144 12. Silverman MG, Ference BA, Im K, et al. Association between lowering LDL-C and cardiovascular risk reduction among different therapeutic interventions: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2016;316(12):1289-1297. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.13985 13. Ference BA, Kastelein JJP, Ginsberg HN, et al. Association of genetic variants related to CETP inhibitors and statins with lipoprotein levels and cardiovascular risk. JAMA. 2017;318(10):947-956. doi:10.1001/jama.2017.11467 14. Ference BA, Cannon CP, Landmesser U, Lüscher TF, Catapano AL, Ray KK. Reduction of low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol and cardiovascular events with proprotein convertase subtilisin-kexin type 9 (PCSK9) inhibitors and statins: an analysis of FOURIER, SPIRE, and the Cholesterol Treatment Trialists Collaboration. Eur Heart J. 2018;39(27):2540-2545. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehx450 15. Gaba P, O’Donoghue ML, Park JG, et al. Association between achieved low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels and long-term cardiovascular and safety outcomes: an analysis of FOURIER-OLE. Circulation. 2023;147(16):1192-1203. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.122.063399 16. Gao Y, Shah LM, Ding J, Martin SS. US trends in cholesterol screening, lipid levels, and lipid-lowering medication use in US adults, 1999 to 2018. J Am Heart Assoc. 2023;12(3):e028205. doi:10.1161/JAHA.122.028205 17. MerativeMarketscanClaims Linked with Lab Data, 2019-2022, 12 months continuous data for each patient (6 months LB and 6 months LF from 1st observed statin treatment). 18. Ambrosy AP, Yang J, Sung SH, et al. Triglyceride levels and residual risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease events and death in adults receiving statin therapy for primary or secondary prevention: insights from the KP REACH study. J Am Heart Assoc. 2021;10(20):e020377. doi:10.1161/JAHA.120.020377 19. Lloyd-Jones DM, Morris PB, Ballantyne CM; Writing Committee, et al. 2022 ACC expert consensus decision pathway on the role of nonstatin therapies for LDL-cholesterol lowering in the management of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk: a report of the American College of Cardiology Solution Set Oversight Committee. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2022;80(14):1366-1418. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2022.07.006 20. Steg PG, Bhatt DL, Simon T, et al. Ticagrelor in patients with stable coronary disease and diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(14):1309-1320. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1908077 21. Wong ND, Zhao Y, Quek RGW, et al. Residual atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk in statin-treated adults: the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. J Clin Lipidol. 2017;11(5):1223-1233. doi:10.1016/j.jacl.2017.06.015